The Women's Six Nations, 2007-2022

A visualisation of match data using Tableau

The Motivation

After a discussion about the RFU’s mission to host a standalone Women’s Six Nations fixture at Twickenham ahead of trying to fill it at the 2025 Rugby World Cup final, and a wider discussion about attendance at Allianz Premier 15s matches, I found myself interested in tracking the growth of women’s rugby, particularly women’s internationals.

Although tracking growth at women’s Rugby World Cups (known as the Women’s Rugby World Cup until 2019, where it was renamed the Rugby World Cup and distinguished from the men’s by year rather than gender designation) would have provided some insight, I decided that tracking the Women’s Six Nations would be more productive, for a number of different reasons. Firstly, the nature of the competition as an annual event allows for a finer-grained tracking of growing interest than the RWC, which only happens once every four years. Secondly, the participants have remained consistent since 2007, when Italy replaced Spain to bring the competition in line with the men’s game. The final key reason to use the Women’s Six Nations over the RWC is that the same six countries host the matches every year, making year-on-year attendance data much more comparable than world cup attendances, since social acceptance of women’s rugby as a sport varies depending on which country it is being played in. Here, we can compare growth for each country, and between countries that are geographically and largely culturally similar.

The Dataset

The dataset was gathered and organised by hand, and the full version of the data is publicly available on Kaggle. Match dates, scores, and results were gathered using Wikipedia match information. Attendance data proved the most difficult to gather, and relied on a number of sources, including English and Italian Wikipedia, but also various rugby stats and rugby journalism sites. Largely, I found these on my own, but I was directed towards Italian Wikipedia as a source by a helpful user on the r/rugbyunion subreddit, who took an interest in using the data and helped me to find some missing stadium records from 2008 and 2011. Regions for the stadiums were collected by hand.

The data does not include information about who won in which year, as this should be calculable from the scores and winners, and overall series wins was not an aspect that I wanted this dataset to cover, as I was more interested in match scores and attendance per match rather than series information. Similarly, information about teams, how points were scored, and timelines are not part of this data, as this dataset was not intended to show a play-by-play retelling of the matches. Tournament information has been included in the analysis of the match data, but this is from the table provided on Wikipedia, to save having to calculate it from the present data (although possible).

Although the attendance data is incomplete, I can pretty safely say that this is the largest publicly-available collation of Women’s Six Nations attendance data. It was not intended to be the case, but it turned out that although a fair bit of this information has been recorded, it has not been recorded in one place, and this dataset helps to overcome this.

So, What Can We Learn about the Women's Six Nations?

Match Data

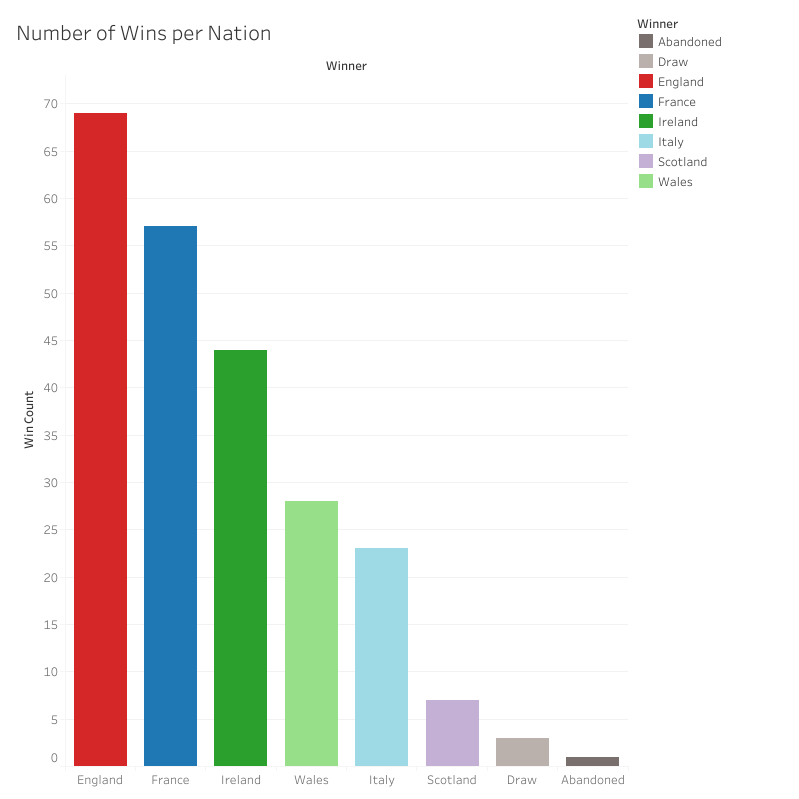

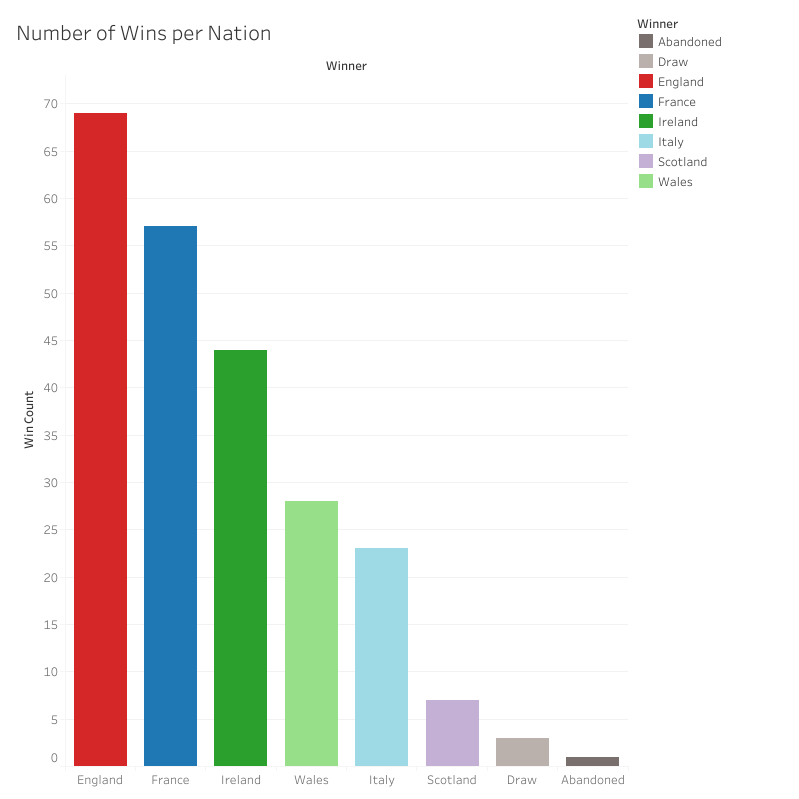

Before exploring the attendance data, I explored the match data, looking at which teams won the most, and where these wins occurred. The first graph I created using Tableau was a bar chart, showing the number of wins per team (home or away). In total, 232 matches have been played since 2007, with England winning 69 of those (a staggering 29.4% of all matches played). France follow with 57 wins, then Ireland with 44, Wales with 28, Italy with 23, and Scotland with 7.

Three matches ended in a draw: Italy versus Scotland in 2010 (6-6), Italy versus Wales in 2019 (3-3), and Scotland versus France in 2020 (13-13). Matches that were rescheduled due to COVID were included in the dataset on the dates to which they had been rescheduled, and those that were cancelled in advance due to COVID were not included at all. One match in 2012, where Ireland played Wales, was abandoned halfway through due to a frozen pitch, and this was included, as the score was recorded as 10-3 and marked as Abandoned. The match was replayed two months later, and Ireland beat Wales 36-0. In this period, only Ireland and England have not drawn a Six Nations match.

The quantity of match wins does indeed correspond to the number of series wins: England, who has won the most matches, has dominated the Six Nations, winning 11 times. France follow England with three series wins, and Ireland with two. Wales, Italy, and Scotland have never won a Six Nations title, although Wales won the Triple Crown in 2009, the only time that England has won the Six Nations and been denied a Grand Slam (the Grand Slam and Triple Crown were not contested in 2021 due to the reduced format of the tournament due to the COVID-19 pandemic).

Corresponding with the number (or lack thereof) of wins is the wooden spoon winner. Scotland have earned the most wooden spoons in the period 2007-22, coming last on 9 occasions (the wooden spoon was not awarded in 2020 due to the competition not being completed due to COVID). Wales and Italy, more similar in wins than the other teams, are tied for number of wooden spoons, each earning three in the period 2007-2022.

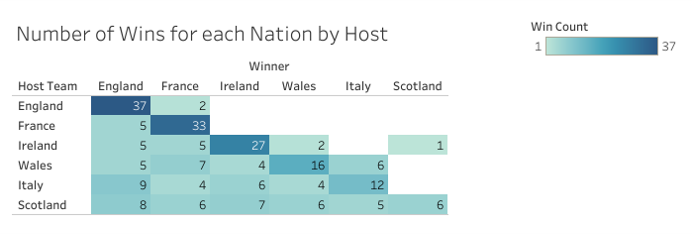

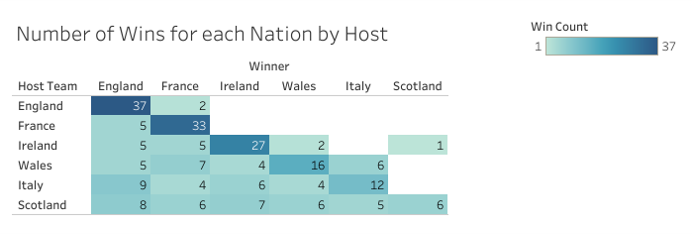

When the number of wins is tabulated with which team played host, we can see a clearer picture of where these wins were achieved, as well as which teams have failed to beat others. All nations are more likely to win at home; England won 37 home matches compared to 33 away matches, France won 33 compared to 24, Ireland 27 to 17, Wales 12 to 11, and Scotland 6 to 1. This data also shows us that England and France are the only nations to have won away to all five other nations. Ireland and Wales have not won away against England or France; Italy has not won away against England, Ireland, or France, and Scotland has only won away once, against Ireland.

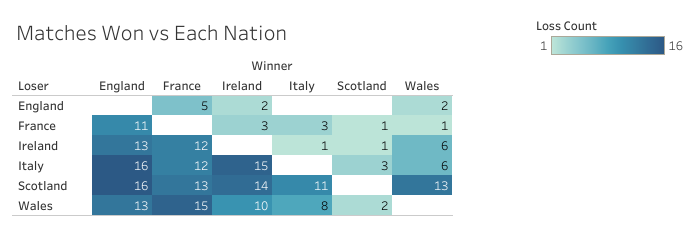

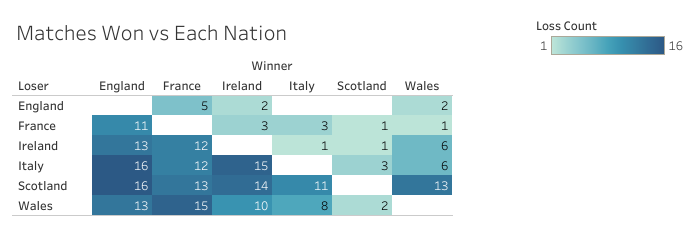

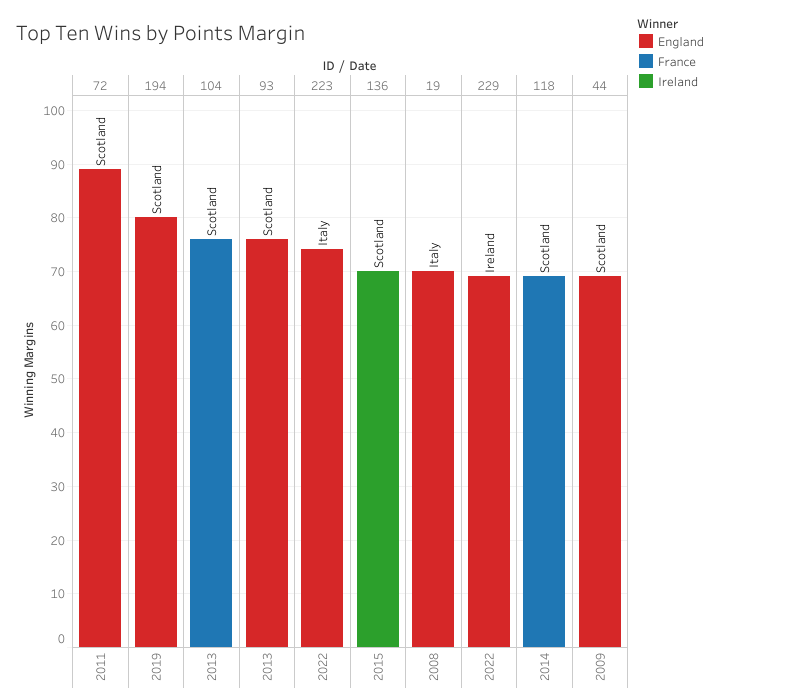

When the wins are broken down according to which team the winners beat, we can see that Italy and Scotland have never beaten England, the only cases in which a team has not been beaten by another in this period. Italy has only beaten Ireland once, Scotland has only beaten France and Ireland once, and Wales has only beaten France once. Scotland has far and away lost the most matches, losing a total of 67 matches in comparison to only 6 wins, a discrepancy of over 11 times as many losses as wins. England, on the other hand, have won 7.6 times more matches than they have lost. This vast difference between nations of winning and losing matches becomes even clearer when we look at the matches with the biggest winning margins; of the top 10 matches with the biggest margins (all wins by 69 points or more), 7 of these wins belong to England, and 7 of the losses are for Scotland. Italy and Ireland both have losses in this top 10, and both teams lost to England: Italy lost by 74 points in 2022 and 70 points in 2008, and Ireland by 69 points in 2022. Apart from England, only Ireland and France have recorded wins in this top 10, all of which were against Scotland (France winning by 76 and 69 points in 2013 and 2014 respectively, and Ireland winning by 70 points in 2015). Overall, this graph shows us an extended period of English dominance, with perhaps a period of French and Irish teams gaining ground around 2013-2015.

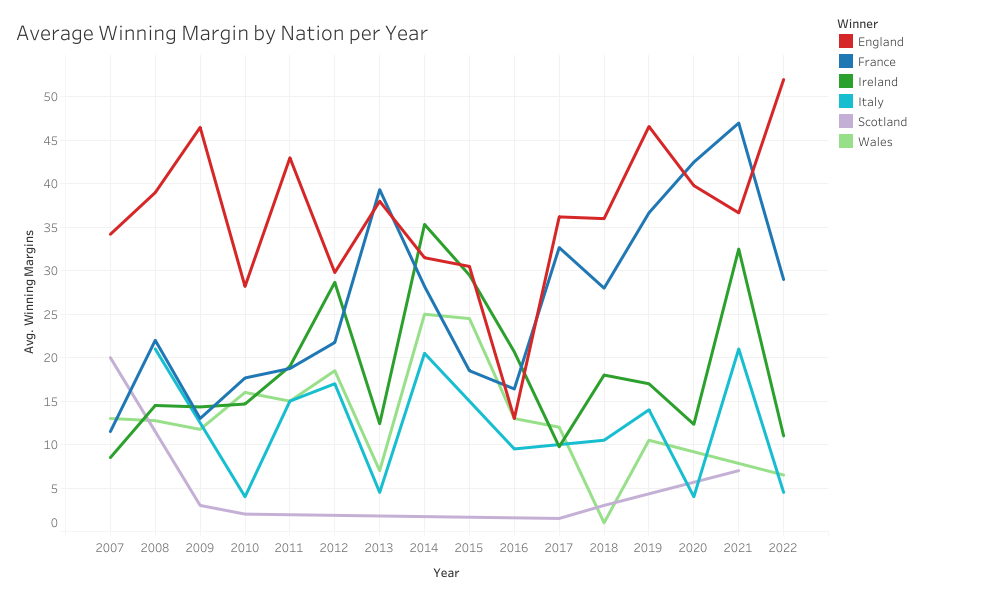

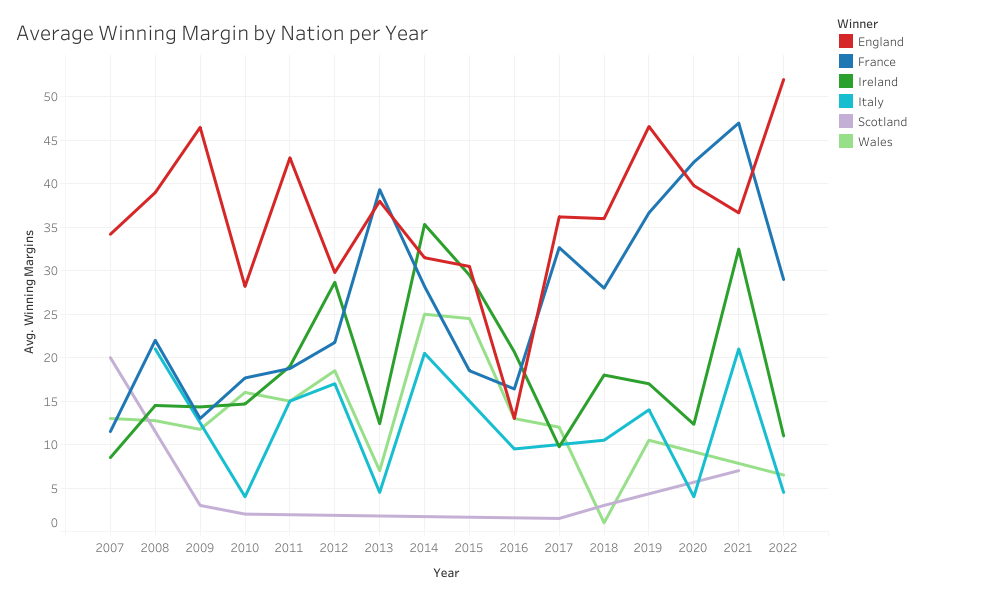

Indeed, when we look at the average winning margin margins by year, we do see a dip in the average winning margin for England in this period, and this corresponds with the years in which England did not win the Championship (2013-2016 and 2018). Interestingly, England won the Rugby World Cup in 2014, beating Canada 21-9 (losing in the final to New Zealand in both 2010 and 2017), so this dip in performance could be related to a shift in priority towards the World Cup.

The average winning margins may also tell us the story of the changes in the sport. Barring Scotland, the gap seems to have narrowed between England and the rest by around 2014, but widened again in the 2016/17 season, where English women’s players started to be awarded professional contracts, becoming the first fully professional international women’s side in 2019. France have followed a similar trajectory to England, becoming fully professional in the same year, and this becomes visible in the results from 2017 onward, with English and French players able to dedicate more time to training and recovery than the other nations.

This may yet change, as the visibility of the 2021 Rugby World Cup (played in 2022) and increasing interest in women’s rugby at a club and international level (with women constituting nearly a third of players worldwide), has prompted several unions to begin to award contracts to their players. In December 2022, Scotland awarded professional contracts to 28 of its women’s internationals. In January 2022, Wales awarded an initial 12 professional contracts, with 25 more contracts added in March 2023. In Italy, 25 professional contracts were awarded in April 2022, ahead of the World Cup that year. Ireland has awarded some contracts to female players, but predominantly those on the Sevens team; of the 29 contracts, 10 belonged to XVs players at the launch of their high-performance centre in November 2022.

The comparative reluctance from the Irish team to award contracts may begin to show in points margins over the next few years, unless there is a change. Even since the recent contracts from the other nations, Ireland has started to fall behind; after qualifying for the Rugby World Cup every year since the competition began in 1994, they failed to qualify for the 2021 (played in 2022) competition in New Zealand, where all five of the other Six Nations teams did. Following this, it may be possible that Ireland are set for a wooden spoon in the competition, and this will be a call to action to invest in Irish Women’s Rugby, following the Senior Men and Men’s U20s both achieving Grand Slams in their respective Six Nations Competitions in 2023.

Attendances

Apart from exploring the historical results, we can track the growth and future of women’s rugby by exploring how attendance data has changed over time. As the investment has increased and results have started to reflect this investment, promotion to and interest from new audiences has also increased. When the available recorded attendance figures are averaged for each year, there is an indication of a gradual increase in attendance from 2007 onwards. Only in 2021 was an attendance of zero recorded: this was the result of the COVID-19 pandemic: all other missing bars in the chart below result from missing attendance figures. Average figures must be taken with a grain of salt, too, since not all matches have a recorded attendance

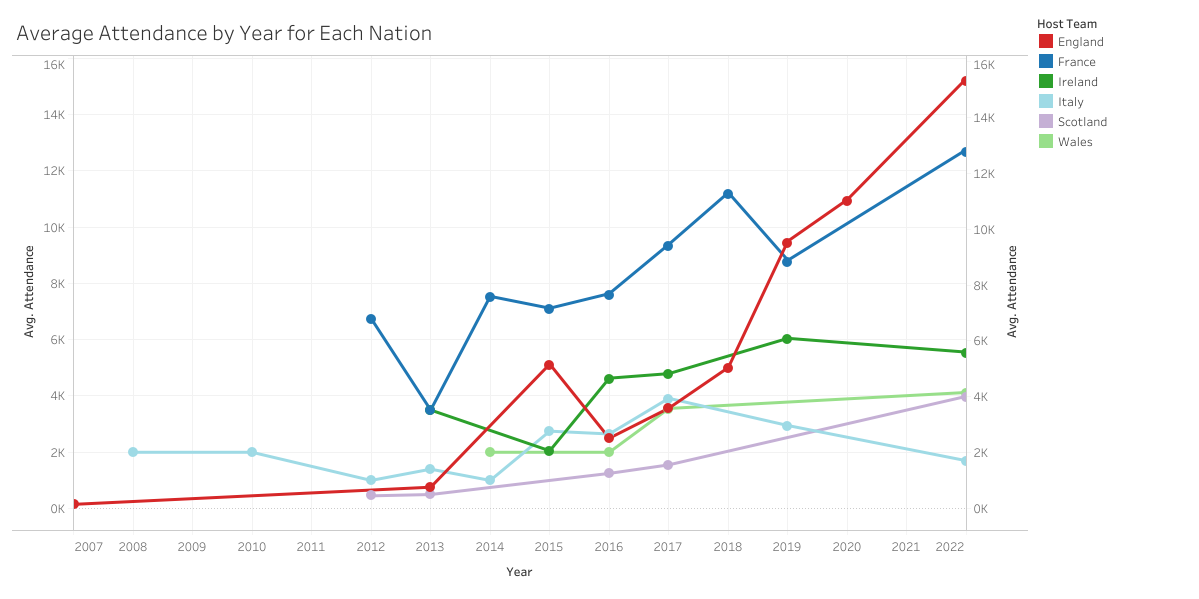

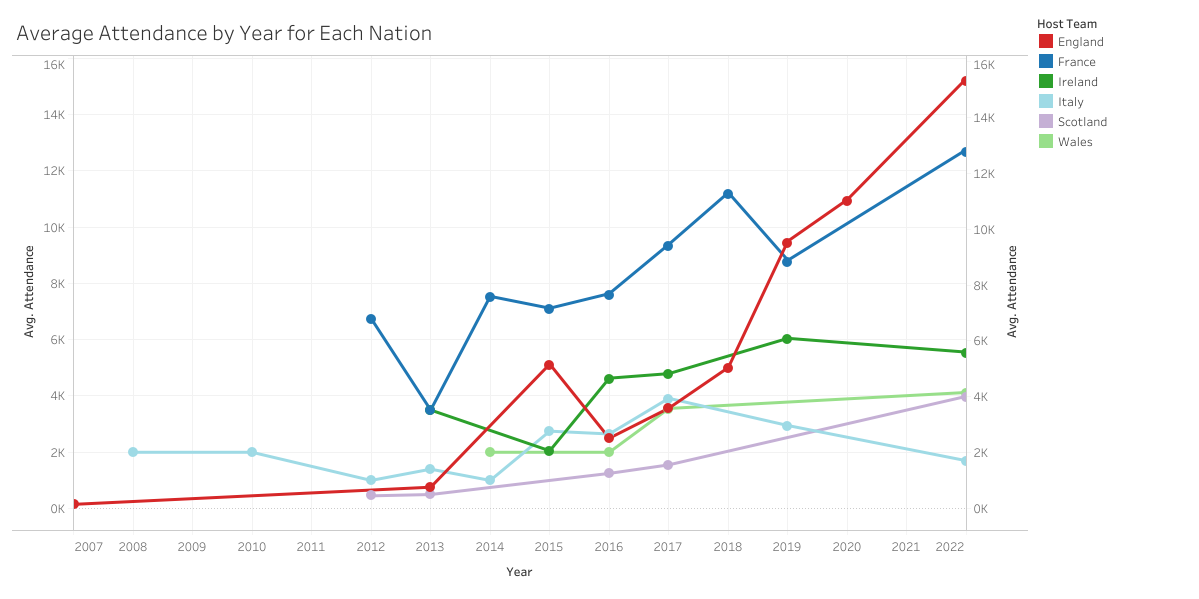

When the attendances are broken down by nation (the dots represent years for which there is attendance data), the increase in interest becomes clearer to understand, and interest in attending Women’s Six Nations games is shown to vary greatly by country. Perhaps as expected, the leaders in attendance since 2019 have been England and France, correlating with both teams professionalising. France, before being edged out by England at this time, led for the highest-attended matches, with 17440 attending a match against England at the Stade des Alpes in 2018, a record attendance for the Women’s Six Nations that still stands prior to the 2023 competition. Attendance has gradually been increasing in Scotland, for whom there is little data, but there has been a near ninefold increase over 10 years, from the average of 453 in 2012 to 3988 in 2022.

Ireland, Wales, and Italy have not seen consistent increases like England, France, and Scotland have. While Ireland saw an increase in average attendance in 2016, the year after winning their second Six Nations Title, there has only been slight year-on-year growth in terms of attendance. Similarly for Wales, there have been slight increases since 2008, but nothing along the lines of the increases seen even for Scotland. Italy seemed to show signs of growth between 2012 and 2017, but it seems that this increase has not continued beyond.

It is clear that professionalism has bolstered attendance numbers, and it will be interesting to see how the recent increases in the number of professional contracts impacts the visibility, quality, and attendance of women’s rugby in the respective countries. Given the awarding of significant numbers of professional contracts for Wales, Scotland, and Italy between the previous and current Six Nations championship, it might be expected that attendance numbers for these three nations will increase more greatly than attendance might increase for Ireland.

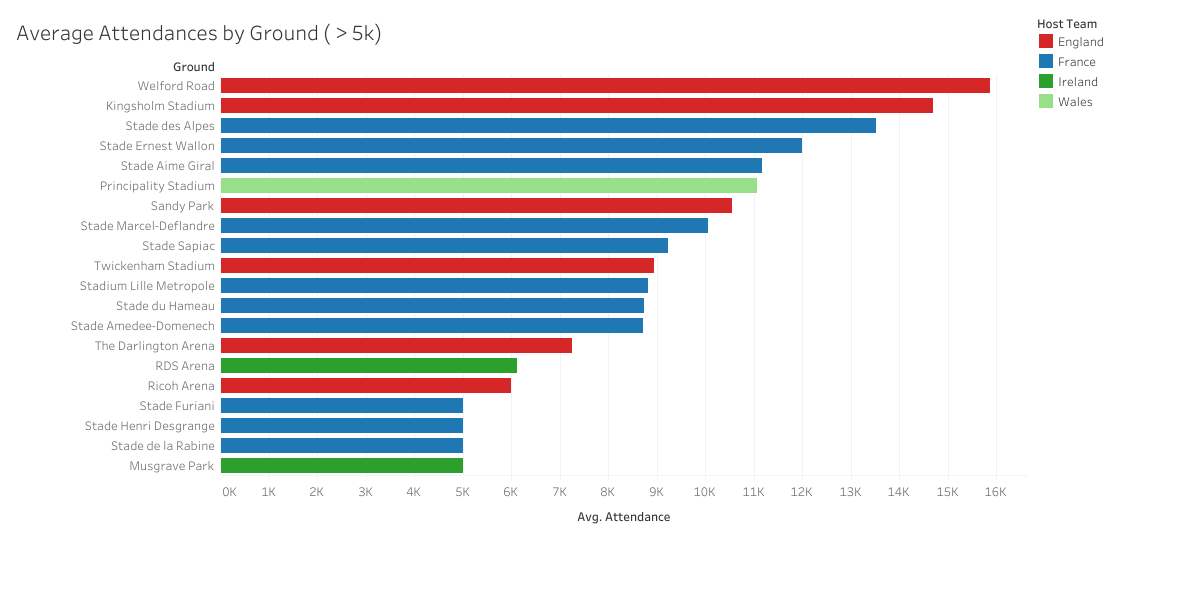

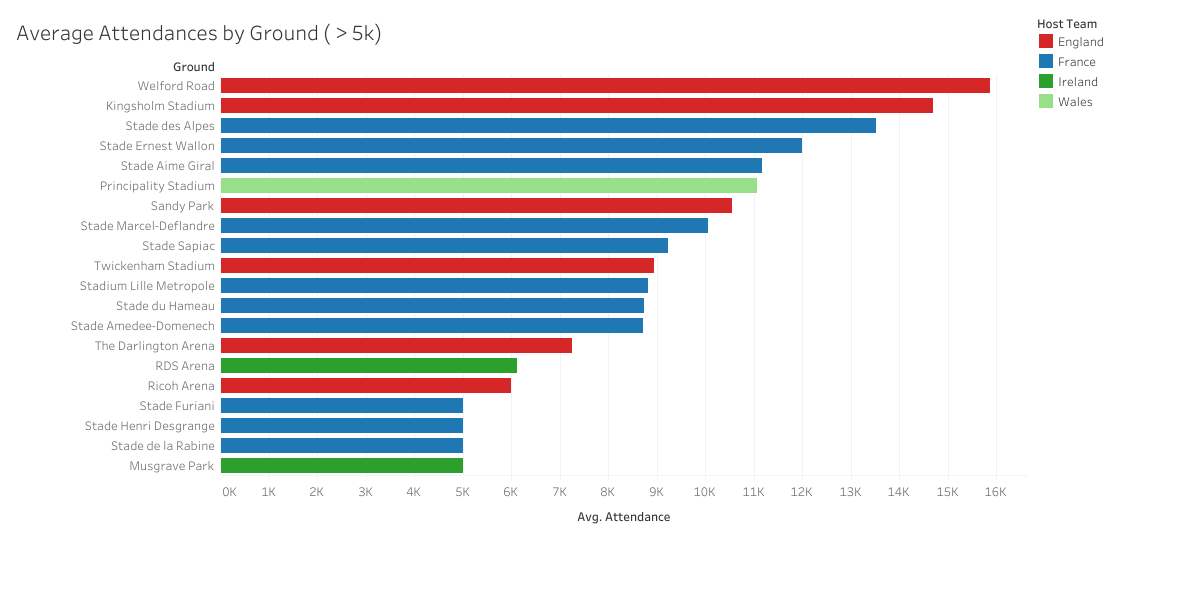

How have France historically fielded such high attendances, even when attendances for the other five nations were so low? Exploring where France has held its matches can reveal the answer, and the emulation of this model by England in recent years can also help explain how the two countries have leveraged the increased quality of their teams to improve attendances. Of all of the grounds which have received an average attendance of over 5000 (of which there are 20), 11 grounds have been in France, 6 in England, 2 in Ireland, and 1 in Wales. It must be noted that attendances in this period for the Principality Stadium (Wales) and Twickenham Stadium (England) have been recorded as estimates when the games have been held following Men’s Six Nations matches as free-to-enter or included in the ticket price, and have not been standalone events. If we explore only standalone events, then England have only 5 of the attendances over 5000, and Wales have none. What France has consistently focused on is not putting the games in the largest grounds, but putting the matches in areas that are strongholds for the sport. Of these 11 grounds with attendance over 5000, only 2 (Stade Lille Métropole and Stade de la Rabine) have been in the Northern half of France, and all the other high attendances have been in the Southern half of France, where the vast majority of Top14 and Pro D2 teams reside.

It is no coincidence that the highest-attended English Women’s Six Nations matches have been in traditional rugby strongholds. All of the best-attended standalone Women’s Six Nations grounds, bar the Darlington Arena, have been at grounds with Premiership Clubs (and therefore strong rugby fanbases). Welford Road, home of Leicester Tigers, holds the English attendance record after hosting 15863 fans at the ground in 2022. This is closely followed by Kingsholm, home of Gloucester Rugby, where 14689 watched England play Wales in 2022. Exeter Chiefs’ Sandy Park hosted 10545 in 2019, the first concerted effort from the RFU to put rugby where the fans were. Other grounds, such as Esher RFC, home of England Women for several years, achieved no such attendances, and even when Twickenham Stadium hosted England Women for double headers, average attendance has not matched the standalone fixtures in traditional rugby strongholds.

The 2023 Women’s Six Nations are set to be the best-attended yet, thanks to the increases in professionalisation and pushes to promote the women’s game following the World Cup. Although official numbers will not be released until after the games, the England vs Scotland match at Kingston Park (home of Newcastle Falcons and more accessible to both Scotland and England fans than matches in the South of England) has sold out. With a capacity of 10200, this match would be well over double of the previous average for England versus Scotland fixtures in England, which was 4179. This figure is massively helped by the 2019 fixture, which was held as a double-header with the men’s tournament at Twickenham. Averaging the available standalone fixtures puts attendance at 2360, meaning that this year’s match attendance is set to be 4.3 times greater than the previous average. The England versus Italy match at Franklin's Gardens in Northampton, which has a capacity of 15249, has sold the majority of seats. As part of the RFU’s ambitious attempt to fill Twickenham Stadium for a women’s match before the RWC final in 2025, the infamous “le Crunch” between England and France will be held at Twickenham Stadium as the very first standalone women’s fixture there, and has already sold in excess of 40000 tickets. Even if Franklin's Gardens were 75% full, and Twickenham only filling 40000 of 82000 seats, the average attendance for England home matches this year would be over 20500, which is a huge increase from the average of 15276 recorded for 2022.

Wales set a standalone home fixture record of 4875 versus Scotland in the 2022 competition, and are anticipating this record to be broken in at least one of their matches being held at Cardiff Arms Park, which has a historical average attendance of 3072 for the Women’s Six Nations, but a capacity of 12500. Scotland appear to have sold a majority of seats for their opening home fixture against Wales at the DAM Health Stadium (home of URC side Edinburgh), which has a capacity of 7800. Again, even if 75% full, an attendance of 5850 would far exceed the 2022 average attendance of 3988. It is unclear yet how many tickets have sold for Ireland’s home games, which are being played at Musgrave Park (home of Munster Rugby; capacity 8008), and the case is similar for Italy, whose home games are being played at Stadio Sergio Lanfranchi (home of Zebre Parma; capacity 5000).

The average overall attendance for the whole of the Women’s Six Nations from 2007-22 is 4446, and the vast majority of (but not all) matches being played this year are set to exceed it. The marked increase in interest in the women’s game, spurred on by the Rugby World Cup 2021 and aided by the increase in professionalisation both in domestic leagues and international teams, heralds a new era for the sport, and potentially a far more competitive championship this year, particularly between first and second (England and France), and third, fourth, and fifth.

Predictions for the 2023 Championship

Based on how data on professionalisation and attendance impacts winning margins, as well as historical data on team performance from 2007-22, my predicted final standings are:

- England

- France

- Wales

- Italy

- Scotland

- Ireland

In my opinion, third, fourth, and fifth will be the most tightly contested, and Wales may edge out Italy in a tightly-fought match between the two. Scotland, although advancing in professionalisation, has more catching up to do than Italy and Wales, although the RWC 2021 match between Wales and Scotland was decided by a last-minute kick from Keira Bevan, so it is also all to play for. Ireland, given the lack of investment into professionalisation, and the failure to qualify for the RWC 2021, seem relatively certain to come last in this year’s competition, although the recent storming win in the Celtic Challenge Cup (featuring development sides from Ireland, Scotland and Wales, with many going on to play for the national squads in the Women’s Six Nations 2023) may indicate potential to cause a surprise upset, or at least knock Scotland back into wooden spoon territory.